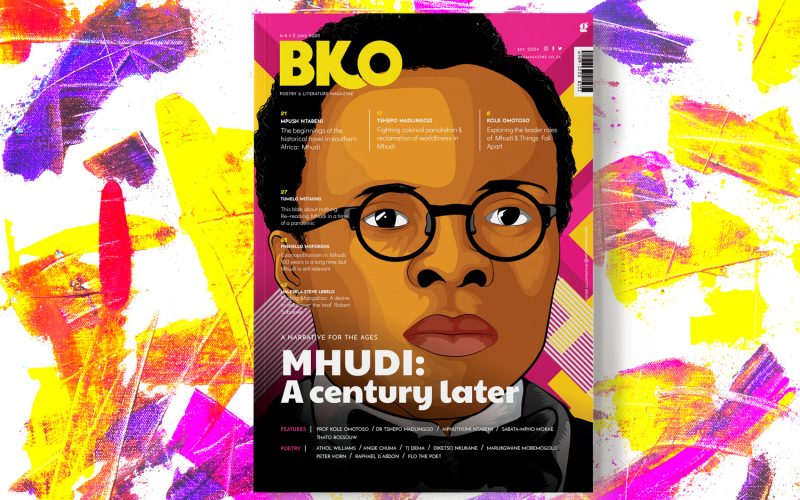

Mhudi was written in 1919 and 1920 by the towering Solomon Tshekisho Plaatje (1876-1932) during his second stay in England. It was the first English novel by a black South African. This edition of BKO is an official opening of the celebrations of Mhudi’s impressive effect on literati and mere mortals the world over.

These celebrations include the publication by Jacana Media of a volume essays later this year titled Sol Plaatje’s Mhudi: History, Criticism, Celebration, edited by Sabata-mpho Mokae and Brian Willan with contributions from imminent scholars including Antjie Krog, Chris Thurman, Zakes Mda, Karen Haire and Lesego Malepe.

This edition of BKO is special because it pays a massive tribute to a narrative that defined the legalised land dispossession of black South Africans in their land of birth by an unjust government.

Though completed in 1920, Mhudi was only published for the first time in 1930 by Lovedale Press. Mhudi came hot on the heels of another perennial book of Plaatje’s – Native Life in South Africa. Native Life decries the passing of Native Land Act of 1913. Set in the 1830s, Mhudi is a romantic story of Mhudi and Ra-Thaga, against the backdrop of a bloody war between Mzilikazi’s Matebele and Barolong in Kunana (present-day Setlagole in the North West). Plaatje had described Mhudi as “a love story after the manner of romances, but based on historical facts”.

Very much aware of how important writing this novel was, Plaatje wrote in the foreword: “South African literature has hitherto been almost exclusively European”. This agrees so much with Chinua Achebe’s assertion that the African writer exists because the telling was done about him, he did not like the telling and decided to do the telling himself. In the famous tale of the hunting where praises are heaped on the hunter because the lion had no storyteller, by writing Mhudi and other works Plaatje assumes the role of the lion’s own storyteller. In other words Mhudi epitomises raison ‘dêtre for the existence of the African writer.

In many ways, Mhudi is a sequel to Plaatje’s Native Life in South Africa. It is also an important book in the historical timeline of literature in the world. In the introduction to the 2019 Strandwolf edition of Mhudi, Matthew Blackman argues that “the novel is in many ways a repository of Plaatje’s socio-political thought”.

In Sol Plaatje’s Mhudi: History, Criticism, Celebration Brian Willan writes that the “evidence suggests that there is a close connection between the two books, Plaatje was working on both at the same time, and drafts of each appear in the same notebook”. Willan adds that the novel “represents a fictional exploration of the political campaigning evident in his journalism, and in his famous book, Native Life in South Africa”. Mhudi is a prophetic book and a creative means of dealing with pariahdom and deliberate impoverishment of black Africans.

Quite often a question has been asked about Plaatje’s decision to write Mhudi in English and not his mother tongue of Setswana, for which he had put up an intellectual defence. Few scholars of language and literature, including RM Malope, Shole J Shole and Eilleen Pooe, had gone further to suggest that Mhudi is “essentially a Setswana novel” and that it needed to be retranslated into the author’s mother tongue. While the case for the repatriative translation holds water and the derivation from Plaatje’s linguistic archive in Mhudi is unmistakable, the author was intentional in writing it in English and, in the foreword, stated the reason for such: “The book has been written with two objects in view, viz. (a) to interpret to the reading public one phase of ‘the back of the Native mind’; and (b) with the readers’ money, to collect and print (for Bantu Schools) Sechuana folk-tales which, with the spread of European ideas, are fast being forgotten. It is thus hoped to arrest this process by cultivating a love for art in the Vernacular.”

It is interesting that this centennial celebration happens in the middle of a pandemic. In his essay, Mpush Ntabeni (A Broken River Tent) reminds us that, in 1918, Spanish flu pandemic – just two years before the completion of Mhudi – gripped the world. Ntabeni takes us back to the beginning of the historical novel in southern Africa; while Kole Omotoso (The Combat) assures us that Achebe’s Things Fall Apart passes the classic muster of an African novel that is set so high by Plaatje’s Mhudi. Phehello J Mofokeng (Sankomota: An Ode in One Album) searches for cosmopolitanism in Mhudi and in many ways agrees with Tshepo Madlingozi’s assertion that Mhudi opens an intentional discursive discourse of landlessness and colonial oppression that continues to this day.

Tumelo Motaung’s essay is light-hearted but not coy. In fact, she represents the voice of Mhudi (the character) very well in this centennial celebration. Steve Lebelo’s analysis of Thami ka Plaatjie’s book on another African giant, Mangaliso Robert Sobukwe, is fitting and apt.

As a guest editor, I appreciate the effort of my fellow guest poetry editor of this edition, Marukgwane Moremogolo for his choice of poems in this edition. I also acknowledge the work done by several scholars who have put in a lot of effort in researching, writing and delivering lectures on Plaatje’s works over the years; Brain Willan, Tim Couzens, Stephen Gray, Maureen Rall, Karen Haire, Sekepe Matjila, Janet Remmington and Bheki Peterson, among others.

BKO is an example of what is possible when African creatives, literati and people in general come together to advance their own agenda. It is the culmination of multi-disciplinary convergence of intellect and talent that should be replicated all over the continent. Mhudi is an African narrative for the ages and we cannot wait for others to celebrate its importance before we realise its gold standard.

Being a guest editor of this issue was a tiring, yet fulfilling effort that I would perform again if invited to do so. It is said that those with beautiful hands do not die. Plaatje is alive, through Mhudi and many of his other works.

Sabata-mpho Mokae

Guest Editor

5 comments

Love the relevance of this magazine

Thank you Ntate Maseko. And for your contribution and support

Love the relevance of this magazine

Thank you Ntate Maseko. And for your contribution and support